In the sun-drenched studio on the outskirts of Barcelona, sculptor Elena Vasquez moves with deliberate grace among her works-in-progress. Monumental forms in marble, bronze, and reclaimed wood catch the Mediterranean light, casting complex shadows across the concrete floor. At 45, Vasquez has established herself as one of the most distinctive voices in contemporary sculpture, known for works that combine classical technique with an unmistakably modern sensibility.

Her latest exhibition, "Thresholds," opening next month at the Tate Modern in London, represents the culmination of a three-year exploration of transitional spaces—both physical and psychological. I spent a day with Vasquez in her studio to discuss her creative process, her relationship with materials, and how her childhood in coastal Spain continues to inform her artistic vision.

Coastal Beginnings

Born in the fishing village of Cadaqués, Vasquez grew up surrounded by the dramatic meeting of land and sea. This formative landscape, with its weathered rocks and constantly shifting shoreline, remains a touchstone in her work. "The coast is a threshold space," she explains, running her hand along the curved surface of a marble piece. "It's always in flux, neither fully land nor fully sea. I'm drawn to these in-between states—they hold so much creative potential."

Vasquez's father was a boat builder, and her earliest memories involve watching him work with wood. "He taught me to read the grain, to understand how materials want to behave," she says. "That's still fundamental to my practice—I don't impose forms on materials so much as discover what they're capable of revealing."

"Tidal Memory" (2022), Carrara marble, 120 x 85 x 70 cm

Material Dialogue

Unlike many contemporary sculptors who work primarily with fabricators, Vasquez maintains a deeply physical relationship with her materials. She selects each piece of stone, wood, or metal herself, often traveling to quarries and salvage yards to find exactly the right element for a particular work.

"There's an intelligence in materials that you can only access through direct contact," she insists. "When I'm carving marble, I'm having a conversation with stone that formed over millions of years. That's not something I can delegate."

This commitment to materiality doesn't mean Vasquez rejects technological assistance entirely. For her bronze works, she uses 3D scanning to create digital models that she then modifies before casting. "Technology is just another tool," she says. "What matters is maintaining the integrity of your vision and your relationship with the material."

Exploring Thresholds

The pieces for "Thresholds" occupy the central area of Vasquez's studio—a series of abstract forms that suggest portals, passageways, and transitions. Some are large enough to walk through; others create more intimate apertures that frame particular views or light conditions.

"I became interested in the concept of thresholds during the pandemic," Vasquez explains. "We were all experiencing this extended liminal state, caught between 'before' and 'after.' I started thinking about how to physicalize that experience—how to create objects that embody moments of transition."

The largest piece in the exhibition, "Passage," is a towering bronze archway with an irregular, organic opening. Its surface bears the marks of Vasquez's hands, creating a tactile record of its making. "I want people to feel invited to move through it," she says. "A threshold isn't just a boundary—it's an invitation to cross from one state to another."

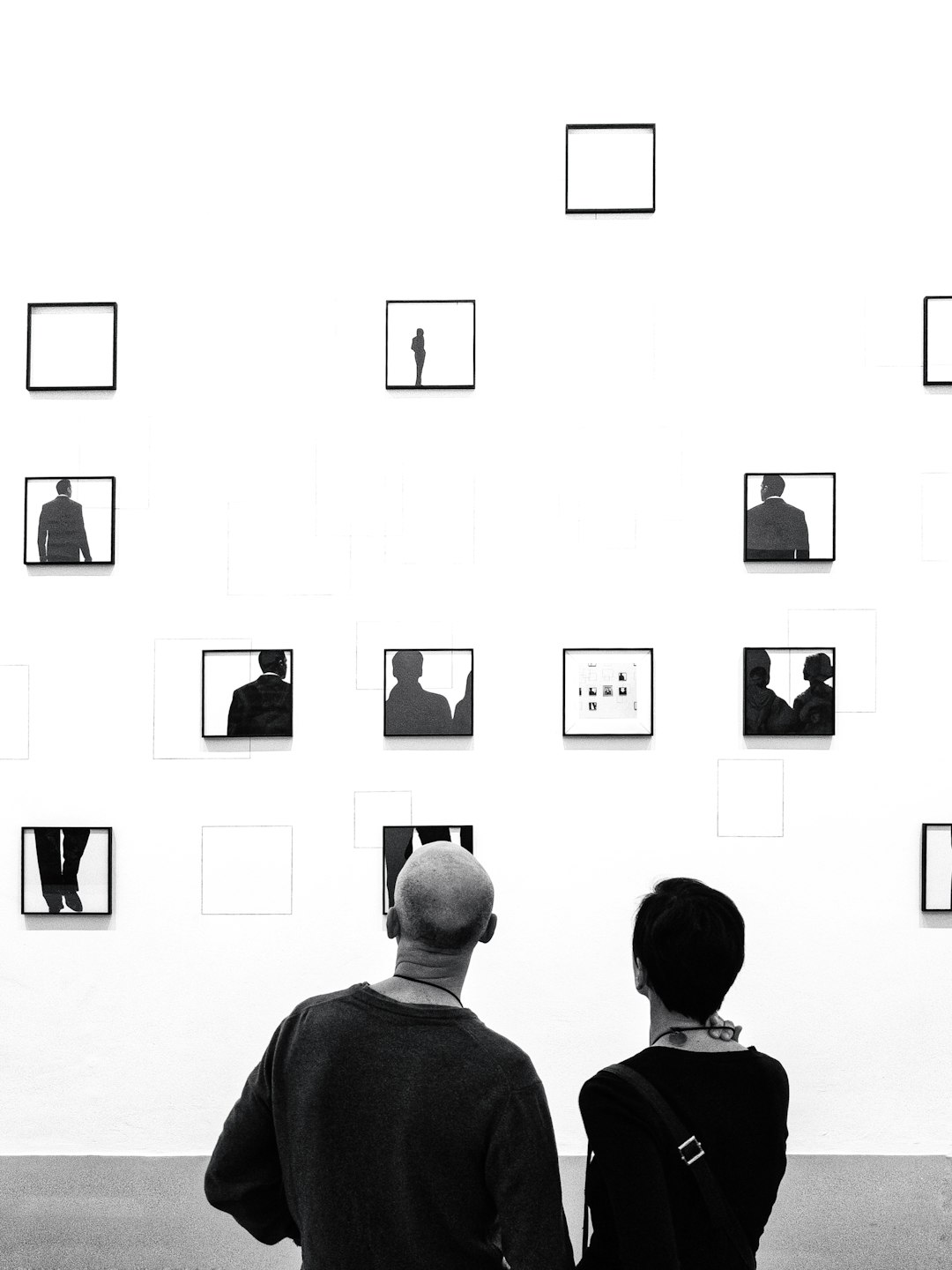

Vasquez working on "Passage" in her foundry

Between Abstraction and Recognition

While Vasquez's work is primarily abstract, it often evokes natural forms—the curve of a wave, the hollow of a cave, the canopy of a tree. This interplay between abstraction and recognition creates a compelling tension in her sculptures.

"I'm not interested in pure abstraction," she says. "I want my work to resonate with bodily experience, with memories of moving through the world. The forms might not be representational in a direct way, but they should feel familiar on some primal level."

This approach is evident in a series of smaller marble works that Vasquez calls "Memory Vessels"—hollow forms with interior spaces that seem to invite protection or containment. "These pieces are about the thresholds between memory and forgetting, between holding on and letting go," she explains. "The negative space is as important as the material itself."

From Barcelona to London

The upcoming exhibition at the Tate Modern represents a significant milestone in Vasquez's career. Though she has shown extensively throughout Europe and the Americas, this will be her first major solo exhibition in a British institution.

"I'm particularly excited about the space," she says. "The Turbine Hall has this industrial grandeur that creates a fascinating dialogue with more organic sculptural forms. And there's something appropriate about showing work about thresholds in London—a city that's always been a crossroads of cultures and influences."

The logistics of transporting the massive sculptures present considerable challenges, but Vasquez approaches these practical matters with the same methodical attention she brings to her creative work. "Each piece has its journey," she says with a smile. "That's part of the story too."

The Viewer's Experience

As our conversation winds down, I ask Vasquez what she hopes visitors will take away from "Thresholds." She considers the question carefully before responding.

"I hope they'll experience a moment of heightened awareness—of their bodies in space, of the quality of light, of the transition from one moment to the next," she says. "Sculpture has this unique ability to anchor us in the physical world while simultaneously opening up imaginative possibilities. In a culture that's increasingly virtual, that physical encounter feels more precious than ever."

Looking around at the powerful forms taking shape in her studio, it's easy to imagine the impact they'll have in the museum context. Vasquez's work commands attention not through spectacle but through a more subtle invitation to slow down and pay attention—to material, to space, to the thresholds we cross in our daily lives without noticing.

"Ultimately," she says, guiding me toward the door as our time together comes to an end, "a good sculpture creates its own gravity. It pulls you into its orbit and changes how you experience the space around it. If my work can do that—even for a moment—then it's succeeded."

Comments (2)

Jonathan Park

April 29, 2023 at 9:15 AMI've followed Vasquez's work for years, and her approach to materiality has deeply influenced my own practice as a sculptor. Can't wait to experience "Thresholds" in person at the Tate. Thank you for this thoughtful interview!

Amelia Foster

April 30, 2023 at 2:47 PMBeautiful interview that really captures the physical and philosophical dimensions of Vasquez's work. I appreciate how she balances traditional craftsmanship with contemporary concerns - something that's increasingly rare in the current art landscape.

Leave a Comment